“The poor you will always have with you” (Matthew 26:11).

Every conversation on the application of Christian values to economic theory will eventually careen into this quotation from scripture. Usually it is produced with an air of triumphalism or at least finality and resignation, taken as a pin to a balloon. Often prefixed by phrases like “after all,” or “anyhow,” its rhetorical packaging not infrequently involves a slight frown, the furrowing of the brow, and a slow shaking of the head. Sometimes, for good measure, there is a shrugging of the shoulders and – amongst its more daring practitioners – a considerate and pained sigh.

The atomized quotation falls like an atom bomb into logical discourse and it seems, at least in this singular case, that sola scriptura rules the day. There will be no questioning the matter: Christ himself has said so: “the poor will always be around” – and that’s the brakes. And isn’t it comforting, anyhow? For when we finish the conversation we’ll usually leave a restaurant and hop into an extravagant vehicle to drive home to a comfortable lodging. Sure, anyone could give more... but why go and impoverish ourselves when we have the very words of Our Lord making it clear that no amount of giving and self-sacrifice will completely solve the problem? We’ll give when we can, but the best we can do after all is pray. We can talk and think all we want about changing society and revolutionizing economics but, “after all, the poor you will have with you always.”

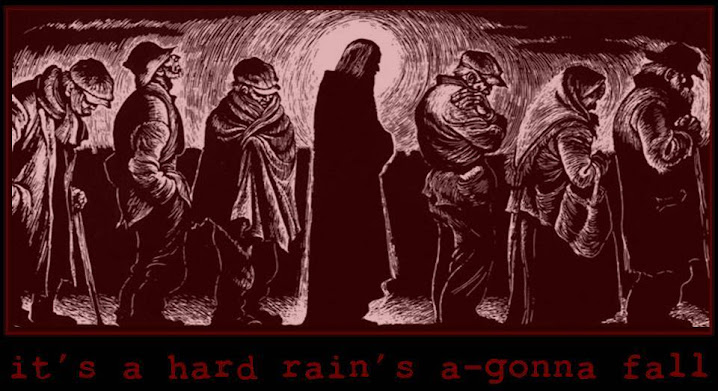

It’s usually at this point of the conversation that I want to fashion a cord whip, overturn the table, and... well, you know the rest. The devil himself can quote the Bible (cf. Mt. 4:1-11); and I am personally become convinced that this little verse is one of his favorites. Too frequently is it hijacked as an excuse for apathy, laziness, or indifference. It is delivered with all of the confidence of a scripture scholar, but rarely with one’s acumen. And while people go on suffering squalor and starvation, our ears ring with this conveniently chosen chastisement of Christ’s, deafened to their plight; yet, the Lord hears the cry of the poor.

First of all, let’s take a deeper look at this quotation. The full sentence is nearly identical in Matthew and John, and runs thus: “The poor you always have with you, but you do not always have me” (Jn. 12:8 RSV; cf. Mt. 26:11). Often forgotten is the small but significant insertion in Mark’s version: “For you always have the poor with you, and whenever you will, you can do good to them; but you will not always have me” (Mk. 14:7 RSV). The weight of this insertion alone is enough to clear up the matter of this verse being used as an excuse. But the thrust of the quotation is the second phrase: “you will not always have me.” What is the meaning of this phrase?

The context in Matthew and Mark both suggest an interpretive placement by the evangelists. Matthew locates this incident directly after the parable of judgment. Christ has just finished describing the criterion for final judgment: the wicked shall be separated from the righteous based on their treatment of the “least” of Christ’s brethren (cf. Mt. 25:31-46). The rationale given has been that, “Whatever you did for one of these... you did for me” (Mt. 25:40). It is after this discourse that the incident at

Mark’s context is also noteworthy. Beginning a few chapters earlier, Christ has been teaching by word and action about the true nature of worship. He has cleansed the

There is still more, and it follows from this juxtaposition of the meaning of “festival” worship. It is argued that the woman’s liberality with the oil should have been spent on the poor. Now, the particular part of Christ’s response which is most frequently quoted (“You will have poor with you always”) is itself nearly a quotation. Turning to Deuteronomy 15, we find directives for the celebration of a “Sabbath year” every seventh year in which debts are to be forgiven and liberality shown to the poor. Here we find it said, “The needy will never be lacking in the land; that is why I command you to open your hand to your poor and needy kinsmen in your country” (Dt. 15:11). The context of the place in scripture to which Christ is likely referring serves to make exactly the opposite point of that one often urged by those quoting Christ. The “festival” in the Old Testament is seen as a time of particular charity toward the poor because of the Lord’s special favor for them; and in the New Testament this idea is illuminated by the revelation that Christ has a special identity with the downtrodden in society.

One final consideration might be brought to bear on this often misused quotation from Scripture, and it is this: rather than using Christ’s words here to defend ourselves who are unjust, why not use them to defend the Lord who is just? There are many reasons for the inevitability of poverty in our world. Some are man-made; others are not. Even the most just economic system (such as that which this website was founded to promote) would suffer from the inevitability of natural disasters such as hurricanes and blights of crops. Despite the best efforts, it would be found that “there will be poor always.” But we will not have made those poor; or, at least, we would have tried our best in solidarity to lift their burden. We would not have made excuses for ourselves by a misappropriation of the Lord’s words; but we will excuse the circumstances of nature which sometimes destroy what we work to build. We would see Christ’s words then as a challenge and a call to continued and sustained effort: yes, there will be poor always, but we would do for them as we would do for Christ were he among us still, spending freely and liberally of ourselves lest we be found guilty in the judgment to come.

An excellent discussion. I had my own view (pun intended) on this topic, which I posted some time ago.

ReplyDeleteIt is sad how often Man is not generous. Of course (by the dicta of subsidiarity, of which more elsewhere!) we do have to be ready to assist others when they appeal for help... but when governments or other "higher" levels of society get in the way of such assistance - this is simply unnatural.

In another writing, not yet posted, another physiological study reveals that the heart "over-pumps" in order to provide a permissive strategy of blood-pressure, so that local areas can manage their own needs... The heart is generous, we minor vessels must be likewise. That reminds me of that terrifying judgement from the mouth of the "Ghost of Christmas Present" about the fat insects on the leaf...

Thanks for some important material for meditation!

--Dr. Thursday

Wow! Great insight, I never really understood that verse though I used it both to defend greed as well as to defend generosity.

ReplyDeleteMuch appreciated.