Certainly, when a country twang is heard on the radio belting out the climax of Silent Night - "Christ the Savior is born" - in early November, it is something of a jarring experience.

But let's be precise. What is problematic in November in this regard is equally irksome on the afternoon of December 24th. It is the premature celebration of the event of Christmas, and this does rightly deserve repudiation by discerning folks who want to keep Christmas well.

But once this primary error has been cautioned against and put in its most exact terms, we're left with a dilemma: what is the alternative? If there's a way properly to prepare for Christmas, then how early is too early to begin this preparation? Is the first Sunday in Advent the benchmark? Or perhaps Thanksgiving, when Santa arrives at Macy's to begin his arduous work?

Let's remember that the liturgical seasons, like the seasons of the year, are somewhat fluid and have semipermeable borders against one another. The season of Advent used to be longer than four weeks, but was also kept as a more intense fast in those days. As such, it was thought that lightening the fast - coming as it did in the dead of winter - was a beneficent thing. This remembrance serves as a double critique for us: first, pointing out that we probably keep our own shorter Advent much more laxly than we ought; and second, indicating that perhaps a longer period of (albeit less intense) preparation for the Christmas Season is in order.

Acknowledging that it is difficult to fix any kind of precise schedule, I'm going to try to indicate what I think is a better plan for how we should approach Christmastide, and supply a general time-frame. This is a recommendation only; hopefully, through my explanations and rationalization of my suggestions, the grounding philosophy behind them will become clear, so that if the proposed dates are disputed, at least the general principles will be found agreeable.

So, when do I recommend beginning to look forward to and even prepare for Christmas? Before Thanksgiving. Certainly not before Halloween? Indeed. Try September 14th.

Now, I know this may seem absurd, but it's not. I think that much of the symbolism and meaning of our Western celebration of Christmas (both the customary and the liturgical) will be enriched if we follow my proposal.

Let's consider for a moment the liturgical year as it reflects the life of the Church and the life of the world. The Exaltation of the Cross, the feast falling on September 14th, is an eschatalogical moment. Although the date of the Feast relates to historical exigencies surrounding the finding of the Cross's relics, nevertheless there may be something more than coincidental in it falling on the octave on the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Mary comes onto the scene, the first "player" in the final act of the Divine Drama of Redemption, and now we get a sort of preview of the climax. The Gospel is about judgment: we either hear Jesus telling Nicodemus that the Son of Man has come to save rather than condemn, or else we hear the stirring verse from John 12 after Jesus has predicted his death: "Now is the judgment of this world, now shall the ruler of this world be cast out."

Now, in mid-September, as the season of Pentecost begins to dwindle and the summer wans, this Feast serves as a watchword for us and a note of expectation surfaces. We have seen in the Easter Season Christ dying and rising again, and with Pentecost was ushered in a new age, of the Church. But Christ promised to come again; He proclaimed His cross as a victory and set us to look forward watchfully to His glorious reign after having cast out the devil.

The Exaltation of the Cross reminds us of this eschatological promise of Our Lord and begins a period of expectancy and preparation which lasts until the Feast of Christ the King (the last Sunday before Advent)*. During that time, we focus on the end times: death, judgment, heaven and hell. For example, we fast for Michaelmas Embertide (at the end of September) and look to that Heavenly Prince to protect us from evil things in the long night of winter. And the relationship with our departed brethren becomes more intense as we look forward to the Feast of All Saints and the month of All Souls. And, coinciding with this development, is the harvest.

In our industrial age, we miss out on the richness of harvest time. In previous times, September saw the earnest use of the cider press while laborers worked under the harvest moon as the daylight dwindled. And then October came on apace, the first frost threatening, and the harvest being gathered into the larders. Of the early grain, a brew was put down to ferment so that the excess would not be wasted, and an Octoberfest was held to clear some of the perishable food and drink to a good harvest. In November, spent grain and more perishable excess could be thrown together for a final bock-brew, and more feasts (whence the traditional Thanksgiving arose) were celebrated from the necessity of consuming what could not be stored and could otherwise go to waste.

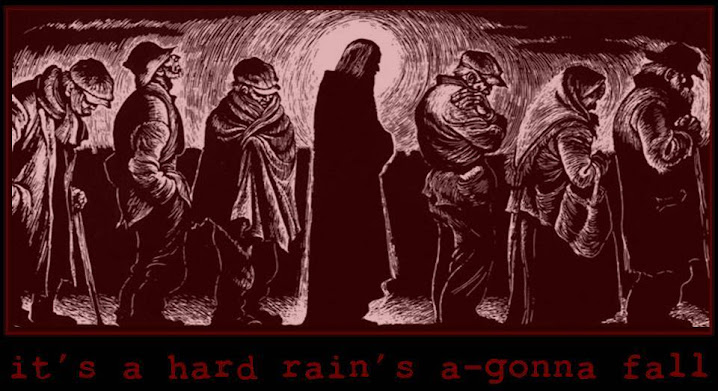

During these times, man passed his days like a long sabbath. The darkness and cold out of doors found families gathered around their hearths for longer hours; games and warming drinks served to pass the time, now that the year's hardest work was past. Pagan lore and superstition abounded, and while the priests encouraged prayers for the dead, peasants quite easily imagined in these dark months that they could see many of the dead stalking the night. For after all, is that not what the Lord had promised? The lessons of Scripture spoke of the end of the world, and an atmosphere of tension throughout the harvest months became more and more palpable. The Lord will return! It was time that men took stock, and had ample opportunity to do so, since they were forced by necessity into their home and around their hearth where the most important things could be found.

As the days grew shorter and shorter, luminaries and evergreens were hung around the home to provide cheer and to serve as a reminder that winters had, historically, come to an end, and hopefully such would be the case with the present one. What with all the talk about about the end of the world, the peasants reserved a little corner of their hearts to look forward with symbols of life - evergreens, light, etc., - to something a little more cheerful as well. And the Church ratified this desire and provided them a focal point: the birth of Christ.

In November, Advent began, and while the eschatological dimensions of the lessons remained, nonetheless the focus on the birth of the Savior came more and more clearly into view. Within an octave of the feast, the "O" antiphons began, their first syllable expressing how the expectancy and anxiety had reached such a pitch that it practically leapt from the throat. And then finally, right around the darkest day of the year, "light shone forth in the darkness" and the great feast of Christmas began. I say began - for it lasted in earnest until Candlemas in early February, when the first real hope of Spring could begin to break through the Winter gloom.

If it takes putting up Christmas lights in October to alert us to the reality of the shortening days, then so be it! If we must hang a bare wreath on our wooden door even before Halloween to ward off the gloom of death which has begun to hang on the wood of the trees - then so much the better, because it shows we are paying attention.

Songs and movies, games and festivals, and the richness of harvest foods ought to be part of this season. Without admitting of Christmas joy too early - which can be easily avoided with a little discernment - still this should be a time of shutting out the world and the dark, gathering our families around our hearth - even if our hearths are televisions and our cheering lights consist of Bing Crosby and Danny Kaye.

If the smell of cider has not begun to permeate our homes by mid-November, then it must be asked whether we have any idea what violent travails Nature is undergoing in solidarity with us. We're not (most of us) farmers who are in touch with the earth. We don't see through our macadam and chemically-embellished lawns that great change has been underway. But this is all the more reason for us to find ways of augmenting our sensibilities so that the full impact of God's creation and the mysteries of the year can bear upon our consciousness.

So, if we have not done so already, let's begin to tune in to the death of the year. Let's begin to deprive ourselves of some of the comforts with which in previous ages it would be a necessity now to do without. And let's make up for that with cider and cocoa and cheerful music so that the poignancy of our fast becomes doubly effective. Let's retreat to the hearth away from the dark and the cold, and begin to look forward to the deadest dark of winter where a light will shine beyond all expectations, toward which it is really NEVER too early to begin looking.

My final word on this is not mine, but Chesterton's:

There is heard a hymn when the panes are dim,

And never before or again,

When the nights are strong with a darkness long,

And the dark is alive with rain.

Never we know but in sleet and in snow,

The place where the great fires are,

That the midst of the earth is a raging mirth

And the heart of the earth a star.

And at night we win to the ancient inn

Where the child in the frost is furled,

We follow the feet where all souls meet

At the inn at the end of the world.

The gods lie dead where the leaves lie red,

For the flame of the sun is flown,

The gods lie cold where the leaves lie gold,

And a Child comes forth alone.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please contribute generously and charitably to the discussion!