In recent comments, President Obama himself acknowledged this force. In an interview following the special election in Massachussettes, Obama offered this analysis:

[T]he same thing that swept Scott Brown into office swept me into office. People are angry and they are frustrated. Not just because of what's happened in the last year or two years, but what's happened over the last eight years.I don't think only a cynic would read into these comments a swipe at the previous administration: I think it's pretty evident. But, no matter: the previous administration deserves its stripes plenty. Nevertheless, I do think it would be naive to name the Bush administration as the effective cause of this spirit of increasing disillusionment with our government and this revolutionary mood building up in movements like the "tea partiers" and the rest. I think, rather, that the national tragedy of September 11th, 2001 would be a better place to look for the kind of sociological shock and trauma which could feasibly cause the existential angst so many are feeing today. I predict that historians and anthropologists a generation removed from us will be able to look back with more clarity and will likely analyse that event as a signal one for many changes in our society, good and bad.

I have my reservations about Scott Brown's victory in Massachusetts. I do not see it as the great ideological monument that others have euphorically announced it to be. In fact, I see the Brown-Coakley race as a good case-in-point for why caution is needed in these times.

Most people you talk to about Brown don't know all that much about him. They will be shocked, for instance, to find out that he posed nude in Cosmopolitan in the 1980s. (You can google it if you want confirmation; I don't typically direct people deliberately into what might be an occasion of sin.) Now, I don't think that Brown's decision to bare all in 1982 matters much to his political candidacy for today. He may have been converted between then and now; he might have repudiated his decision publicly for all I know; for that matter, he might secretly have lived as a mafia don in the intervening years. It was a long time ago; many years have passed. My point is that it hardly got mentioned and the sort of vetting and investigation that candidates are usually put through seems to have been swept under by stronger currents in this recent election. Therein lies the danger.

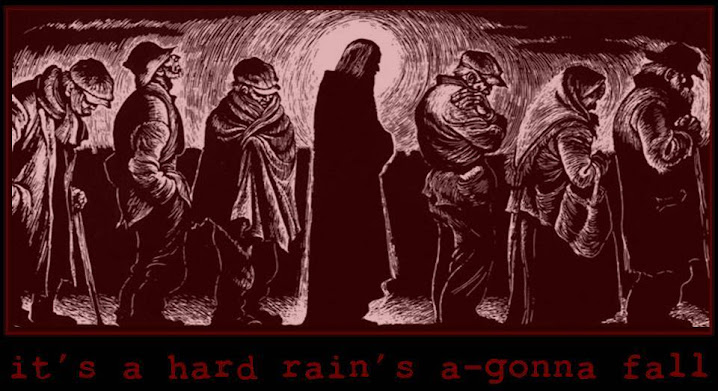

Revolution is a dangerous thing. When I read the President's remarks today, I had to give him credit for his sober insight. And for whatever reason, all I could think of was the motif of eerie footsteps with which Charles Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities symbolizes the dangerous and inscrutable forces of revolution:

Headlong, mad, and dangerous footsteps to force their way into anybody's life, footsteps not easily made clean again if once stained red, the footsteps raging in Saint Antoine afar off, as the little circle sat in the dark London window.The novel, of course, is about the lives of several people who find themselves swept up suddenly in currents that are somehow greater than the sum of all their individual motives. It typifies well the danger and the power of the revolutionary spirit.

Revolution can be merely reactionary. It can be fueled by anger, or fear, or even boredom. And when revolution is such, it is perilous. The Catholic hesitancy to revolution was always based on this insight: that revolution which merely reacts, which bases itself upon the premise that "anything would be better" than the status quo is dangerous and irresponsible. The status quo, at least, is static: it stands. Chesterton also remarked that the world does not progress, it wobbles. And wobbling, it is always susceptible to toppling and to falls. A revolution that blindly seeks to destroy the current state of affairs and does not care with what it shall supplant those conditions may result in nothing more than a crumbled society, a crippled thing that cannot again be made to stand.

Real revolution, Chesterton pointed out, is aimed at restoration. Real revolution - which the Church embraces under different names, such as "conversion" or "reform" - only tears down in order to build something better. Chesterton called this continual process in Christian orthodoxy "the Eternal Revolution."

I am glad that folks are beginning to get angry and to get fed up with the status quo. I am glad that the two-party dominance of American politics has begun to leave a sour taste in many people's mouths. I am glad that they are calling for a greater voice and ability for action within the political process - that they are demanding transparency and accountability.

But we must continue to be vigilant lest we get caught up in anger and forget what we're angry about. We should not be angry mostly because things are organized such and such a way, but because they are NOT organized in some definite, better way. If Scott Brown becomes an ideal merely because he's not Martha Coakley, then we have cause to pause. We must ask ourselves whether we've settled for something less than ideal because it's expedient for the time being, or whether we have temporarily forgotten our grander ideals in the energy of the moment. If there is any hint of the latter sentiment, then that is the dangerous and perilous spirit of revolution sweeping us away down some unknown path. If it is true - and I think it is, at least partly - that the same spirit that swept Obama into office also swept Scott Brown into his seat, well then that is a cunning and wily spirit with a powerful strength to sweep, and it might end up sweeping the legs of our standing Republic right out from under us.

So, caution; vigilance! Let us continue to remember our ideals and to talk about final goals. Insofar as a revolutionary spirit leads us to give our heart over to what could be rather than what is, then it is a wholesome and healthy spirit to be embraced. That spirit will sound in our hearts as an organized marching tune, a rhythm with which we can fall in step and progress towards some definite goal. But let us be wary of the confusion of footsteps that the other spirit of revolution brings: headlong, mad, and dangerous footsteps that may, if we fall into line with them, leave us trampled on the road to nowhere.

Re: the 2-party system and its flaws, could it be that the election of first independent-"party" president (at least in modern history) could end up being a bigger deal than the election of the first "black" president? Wouldn't that be the real signal that racism has ended: that an ideological change is more important than a racial one?

ReplyDeleteWell, I think yes and no, Kevin. I think, in a way, such an election would be more momentous because it would really signify what it represents. Whereas Obama's election as a black man is a more convoluted case. I don't deny the historical significance of its being able to happen, but I think some people might overestimate its significance. They would overestimate its significance if they forgot that elections are no longer really any judgment of the popular sentiment and will of the people. Half our people don't vote, and half that do don't really care.

ReplyDeleteRacism is still a very big issue in our country. Black governors being elected are probably a better mark of progress than a black president, considering that racism is pocketed within certain sectors of our society. It's alive and well in many places, and nearly everywhere there's no sincere discussion of the matter taking place. Even amongst the "progressives" there's this smarmy double-talk of "putting that all behind us." It's like they don't want to talk about it because they don't want to admit it's still an issue. But it is.

We had a brief (too brief) discussion about this recently on the wall of a Facebook Group I've started here. I think there's plenty to be discussed there.

So, let me try and sum up. I think that the election of an independent candidate would signify more than the election of a black man because of how presidential elections work nowadays and what they mean, but not because of the weight of the ideas. In fact, I think racism is the Achilles' heel of many in the conservative (broad) movement (paleo, neo, crypto, or whatever): if you go around talking about freedom from tyranny and want individual rule but don't recognize the subtle oppression that leers and jeers can affect, then there's a hypocrisy that will out one day as all truth must. And it does no good to trot out the old faithful arguments of "welfare is racism" or the like because they end up being a red-herring when what we're interested in is hearts and minds. It's like my mother would say when scolding me for misbehaving at school and I'd keep bringing up the behavior of others: "THEY'RE not my kids. YOU are!"

In short, I don't want to downplay racism, but I do admit that - for a host of reasons - the election of a black president is not a good indicator of the state of racism in our nation. The election of an independent would be a better indicator of the values of small republican rule and personal freedom. But we need to work at this thing from both fronts, and I for one am determined that if home rule and personal freedom ever gain any ascendancy in my day, it will mean everyone's home and everyone's freedom, and freedom not only in a material or legal sense, but from prejudicial assumptions, or even the coercive side-long glance.

A well written and weighty reminder, for I was excited over Coakley's loss and did not grasp deeper implications.

ReplyDelete