Even in more normal moments he seemed to be one who singly pursued a solitary train of thought, and he was still talking, like a man talking to himself, about the rationality of topsy-turvydom.Today, the Second Sunday of Lent, the Church invites us to consider the Transfiguration of the Lord.

"We were talking about St. Peter," he said; "you remember that he was crucified upside down. I've often fancied his humility was rewarded by seeing in death the beautiful vision of his boyhood. He also saw the landscape as it really is: with the stars like flowers, and the clouds like hills, and all men hanging on the mercy of God."G.K. Chesterton, The Poet and the Lunatics

I've always been partial to Mark's account of this event, because of an oft-overlooked phrase at the end of the pericope: "So they kept the matter to themselves, questioning what rising from the dead meant" (Mark 9:10 - NAB).

Now, Mark's Gospel is arguably the one most situated within the "eschatalogical dimension," that is, the one most concerned with the immanence of the Lord's return (although the focus is certainly present to the other Evangelists' accounts, especially Luke's).

The reason that this phrase in Mark particularly strikes me is that, in the immediate context, Christ has just finished emphatically his first prediction of His passion (see Mark 8:31ff). Also, more remotely, Jesus has already been depicted miraculously restoring the daughter of a synagogue official to life (Mark 5:35-42). That the man whom Peter had affirmed to be Christ, the Son of God, was given power even over life and death could not have escaped his followers' attention. So, why the confusion about "what it means to rise from the dead?"

The key to the answer is the meaning of the Transfiguration itself. Six days before the Transfiguration, Christ had been teaching his disciples about the eschaton, and the "coming of the kingdom of God in power":

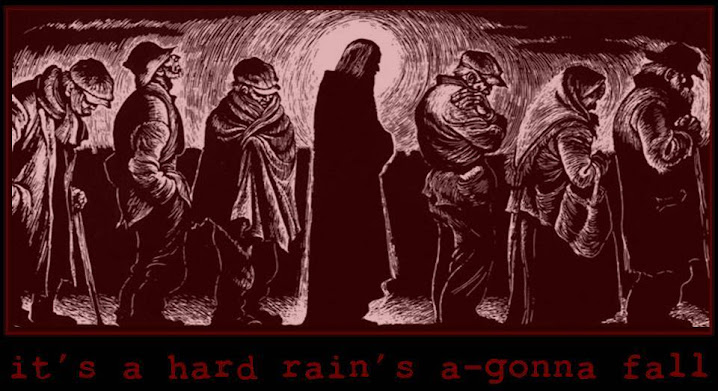

He summoned the crowd with his disciples and said to them, "Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me. For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake and that of the gospel will save it. What profit is there for one to gain the whole world and forfeit his life? What could one give in exchange for his life? Whoever is ashamed of me and of my words in this faithless and sinful generation, the Son of Man will be ashamed of when he comes in his Father's glory with the holy angels" (Mark 8:34-38).Then, on the mountain-top with Peter, James, and John, he provides a glimpse of the glory to be revealed in that day. The root of the question: "What does it mean to rise from the dead" seems to rest in this vision of glory, accompanied by Christ's paradoxical teaching about laying down one's life in order to gain it. This is not mere resuscitation that Christ intends to accomplish for Himself and for all who follow Him: it is not simply the restoration to former life. It is an inauguration of a new being, the recreation of nature in a glorified state, turning inside-out and upside-down all that was once twisted and distorted by sin and death.

In the early Church, this vision became manifest in the witness of the martyrs. Stephen, dying, realizes the eschatological promise of Christ: "He, full of the Holy Spirit, gazed into heaven and saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God; and he said, 'Behold, I see the heavens opened, and the Son of man standing at the right hand of God'"(Acts 7:55-56). Whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake and that of the gospel will save it. Rising from the dead means rising to new life; and it means, first, dying to the world and sin. Resurrection "means" the death of martyrdom, in the sense that an effect "means" or intentionally manifests its cause. Indeed, the vision of Christ glorified on Tabor might even have included a glimpse of His future wounds shining in splendor as they do in Heaven now for eternity.

For the evangelist Mark, the Gospel was meant to shine light and meaning on the sufferings of his present-day community. The persecution by Rome challenged the believers of Christ to place their hopes in the eschatological dimension: to see future glory present in immediate sufferings, to find future gain in present loss. And the Gospel bears this message as meaningfully for us today.

It is really fortuitous that the seasons of Paschal-tide coincide each year with tax season. As we fill out our earnings statements and take stock of our worth, we would do well to ask what we really have "gained" by our year's efforts. Have we gained even the whole world, at the cost of our soul? Have we stored up treasure on earth like the fool in the Gospel, whose life would soon be demanded and find him sorely lacking in the accounting book of Heaven? Or have we acted instead like that other Fool in the Gospel, the Fool for Christ's sakes who bumbled his way along as the head of the Apostolic Church and found himself at his life's end hanging upside-down in a comical testimony to the dramatic reversal brought about by Christ?

The Transfiguration teaches us that Resurrection means death, that hope of future glory can only be substantiated through acceptance of present shame. "What it means to rise from the dead" is to have first died the death worthy of a follower of Christ. It is not only our final end that matters in this regard: it encompasses all the little daily deaths, the denials of self and turnings away from sin.

Of course, the focus of this website is economics and the social order, but this reflection is easily brought to bear in that context as well. As we go about our business these next five weeks of Lent and beyond, we may find that the building up of the kingdom of God here on earth is a drudgery and a plodding affair. Rome was not built in a day. But the kingdom of God in glory shall come like a bolt of lightning out of the clear blue sky, and we must always be ready to stand judgment on that day. Every economizing decision, every political motive, must be informed for Christians by this eschatological focus. The rationality of topsy-turvydom demands reckoning this very day - in our nightly examen, in our filing of our income tax return. May all our testaments in this world, from the lives of our children to the ledgers of our accounts, bear witness to the things which truly matter, to what it means to rise from the dead.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please contribute generously and charitably to the discussion!