In a schoolyard, a game of Simon Says. A boy stands in the middle of a circle of classmates, each of whom has one foot raised in the air, a hand on the head, and eyes tightly shut.

"Open your eyes," the boy says. None do. "Simon says, open your eyes." And their eyes are opened.

The boy, a shrewd young man who is perhaps feeling a little too haughty in his position of arbitrary power, has begun to grow rather bored with the game. To his right sit another half-dozen or so kids who have gotten caught doing or not doing the sundry activities commanded, but none from real inattentiveness: most have deliberately thrown the game to mix things up a bit, to gain a chorus of appreciative laughter and to reinforce the idea that this is fun, after all, what they're doing. But the illusion has lost its power for the boy who is Simon. He is no longer entertained: he sees the absurdity of it all. And so, he contrives his own way to have fun.

In a yawning sort of way, he says matter-of-factly, "Aiighh-ooohaayysmm, put down your foot." Two of the children around him stand down. He points triumphantly, "Ha! I didn't say Simon says!"

"Yes, you did!" Even those who were wise to the ruse feel empathy for the injustice, because they had been as unsure in keeping their feet raised as their fellows had been in putting them down.

"No, I didn't," Simon shouts back, "I yawned. I never said 'Simon says.'" And he smugly folds his arms. Defeated by his certainty, the losers slink off to sit in the row of rejects, muttering under their breath. And, hearing them, another inspiration strikes him.

"Simonssaysdont put-your-foot-down," he mumbles, quickly, with the flattest of intonations, but carefully enunciating the last few words. The remaining three contestants lower their raised feet, and Simon raises his arms in victory above his head. "Ha! I said don't! You didn't hear me, but I said it! I said don't! You're all out! I get to be Simon again," he finishes, turning to the gaggle seated nearby, appealing to them for a new round.

But no one stirs. Eyes all around him aim arrows of animosity.

"It's not fair," one boy complains. "It doesn't make sense if we can't understand you."

"But it doesn't make sense, anyway," Simon tries to explain, wondering to himself how they cannot have been equally disenchanted with the stupidity of the game before his innovations made it interesting again.

"We'll play again," offers another boy, but caveats in a sinister tone: "Only, you can't be Simon."

"Hey, no!" Simon pouts. "If nobody is left at the end, the same person goes again! That's the rule!" Granted, he said to himself, we never had to use that rule: but that was with the old way, the stupid way. But his appeal does not silence the malcontent around him: the other children have seen that rules can be played with, can be improvised.

And so the circle gathers once more around a new demagogue, but Simon goes off to sulk. He has learned a lesson, today; indeed, they all have - a terrible and important lesson about politics and laws, about despotism and democracy, and about the philosophy of rule-making and rule-breaking.

In the news recently, there's been quite a dust-up over an e-book recently posted for purchase on Amazon.com. The work, The Pedophile's Guide to Love and Pleasure: A Child-Lover's Code of Conduct, was of course bound to be provocative. The title alone is enough to make me recoil in disgust; I have no need even imagining what would be its lurid contents. The concept is despicable, and it is a sign of the times in which we live.

But the outcry about the book strikes me as frankly ironic. Perhaps this is some of my cynicism about our culture, but the calls for Amazon to remove the listing and to censure the author strike me as simply inconsistent.

The manufacturers of our culture are constantly doing away with taboos and norms. The popular culture trajectory for the past half-century has seemed to be simply searching out those things which "simply are not done," and doing them. And, having done, promoting them. And having promoted them, normalizing them. And having normalized them, legalizing them. And having legalized them, turning with the same attitude of open-mindedness and tolerance to the things which used to be normal (or normative) and persecuting those instead.

What logical argument can the doyens of our ethical elite possibly mount against this new book, I wonder? How must the author feel hearing their outcry, the same voices that have always and forever been crying out for more license and liberty and the stripping away of taboos, now warning, "No, you can't do that, mate; it's just not cricket"? They have mumbled their commands; he could have sworn he'd heard "Simon Says." And now this sudden changing of the game? And the fact is, when you get right down to it, that his critics have no argument: many of them, at least. They have sown a philosophy of rules and are now reaping its fruits. Isn't the present author simply taking a page out of their book and asserting a strategy they used in the past to make what wasn't done suddenly okay to do?

This is not to say that the author is ultimately right. Of course, he isn't. He's wrong according to the natural law: but they've denied that. He's wrong according the Church's law: but they've abolished that. He's wrong according to men's laws: but they've changed those before. And he's wrong according to cultural sensitivities and mores and commonly held values: but isn't he simply reshaping them as his present critics have so laudably reshaped them in the past?

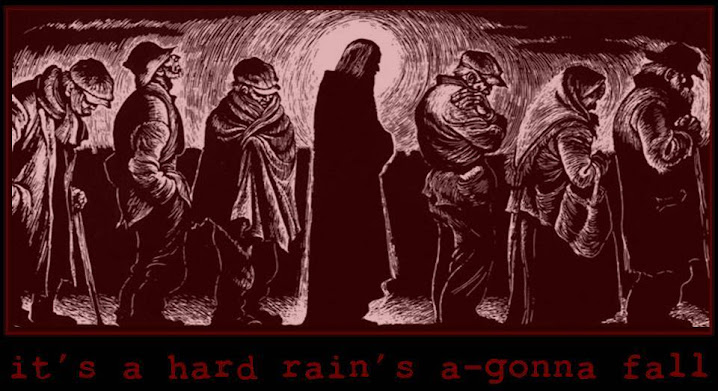

It's a sad, silly state of affairs. It's the state of affairs that moralists and preachers have warned about for years and years. But that's a slippery slope, they were told. "It'll never come to that: that's simply not done; it's just not cricket." But it came to that, and then went past. And then another sticking point, another event horizon, a place at which we'd surely never arrive - see it retreating now in the rear view mirror? Every voice of caution, every prophet who stood to withstand the tyrannical march of progress and social experimentation has been mowed down by their tanks: the academic hierarchy, the Hollywood execs, the bought-off politicians. And the blood that soaks the battleground of the culture wars cries out as eloquently as the blood of Abel: "I told you so."

The lesson of the schoolyard is the lesson today. The author might be the loser today, he's waiting on the sidelines. The present Simons one day may learn how rules can turn against you when once you've shown how to turn them; they may find that their game is suddenly somebody else's.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please contribute generously and charitably to the discussion!