It's been a too-long hiatus here at the blog for me, and I'm going to make an attempt at a comeback of sorts. I've too often made myself a liar by promising levels of consistency and subsequently failing to live up to them, so you will have no such oaths from me today. I'm going to try, that's all.

I'm back today to riff on an old theme with a new variation: cheap, maybe, but the same thoughts preoccupy me this year with the same intensity as in autumns past, and there's something to be said for that. I've written on this same matter in other places: here and here. Personally, I quite like what I wrote there, so you should go read those earlier thoughts if you have the time. Or do not, that's just as well. Anyway, on to the matter at hand...

I stepped in goose droppings today.

In the past week or two, Marquette's campus has been invaded by a flock - maybe several flocks, I don't know (how can one tell these things?) - of geese. Now, I'll admit straight away that I don't know about geese. I don't know why they're here, where they've come from, where they are eventually going. I don't know whether they're flying south from climes that are growing colder to places where it's warm, or whether they're flying north from... well, as I said, I don't know where the hell geese come from. But for my purposes, it doesn't really matter. It is enough for me that there are here, now, on my campus, geese - geese that weren't here before, that were someplace else. The point is that they are here - and they're here n o w. Since I've been at this campus, I've been able to walk its breadth without having to watch out for goose droppings. I could cut across a space of lawn as easily as take the pavement and had not to worry about a suspicious smell lingering around me for the rest of the day. But I can no longer. Now is different than before.

Now is different. I might have noticed, what with it getting colder and darker and leaves falling off trees. In fact, I have noticed - I picked apples a few weeks back, and I've lit a pumpkin pie candle in my apartment because it seems fitting now. Fitting now in a way that it was not before.

But today, I stepped in goose droppings, absenting my attention for just long enough from the treacherous trek to class so that the calamity caught me unawares. I sorted it out quickly enough with a spot of wet turf and what probably looked from afar like a serviceable impersonation of a chicken sorting through a cow-pie for worm larvae. But the event piqued my attention: the change that has been happening all around, that I've noticed but not really attended to became suddenly very real and very important. Where did all these geese come from? Why are they here? What does it all mean?

In ancient times, seers and prognosticators examined the droppings of birds to find cosmic importance. Today, I joined their company. I had been inattentive this autumn to the "end times" manifestation that the Church rather heavy-handedly observes in these days of the liturgical cycle each year. As I wiped the bottom of my shoe today I thought of a line from the Gospel for the coming weekend: "And awesome sights and mighty signs will come from the sky" (Luke 21:11b). Now, surely our Lord had something other in mind than goose droppings. The meaning attains, though. The ancient augers weren't a scientific bunch, but they noticed that birds migrated and that the patterns of their travel meant patterns in their diets (and thus in their droppings). And they tried to make sense of these patterns and to forecast important events. They were inspired by birds' adaptive nature and the way that they modify their lives to fit the seasons. We should have some of the same inspiration.

Now is different than before, but we might not live as though it is. We might not even think differently. But the Church - She who reads the signs of the times so much more reliably than the ancient bird-watchers - the Church wants us to think differently in these days. She wants us to tune in to the eschatological meaning breathed by the Creation surrounding us. Things are here that weren't here before. And things that were here have gone missing.

We tread daily over leaves dead on the ground, but how often does it spur us to think of the bodies that are the dust beneath the leaves: the bodies of loved ones passed on to judgment, who may suffer now in purgation for the sins of their flesh and for want of our prayers? We step around goose droppings, but do we stop to reflect on what it means that such things have suddenly come - out of the clear blue sky - as were not here just a few weeks ago?

Now, it may be objected that this is a fine reflection of the aptness of the seasons of the year to the calendar of the Church, but what about those living in different climates? Well, for those folks - as well as for us who are lucky enough to have nature's help - the Church and culture have provided other ways of marking time. [Of the parishes that elect to decorate their sanctuaries at this time of year with pumpkins and cornucopias, I will not speak for fear of opening a can of worms. Come to think of it though, I think a can of worms could very effectively enhance the sorts of decoration we see so much of during this season: a rotting pumpkin, perhaps, next to a skull, seated nicely in a basket of dirt near a side altar?] But for those of us who wish to attend more deeply to the import of these times, there's plenty to go around: the ember days of September, the building apocalyptic vision of the readings throughout October, the Dies Irae and other mementi mori during November. And from Culture, we have ciders and mulled drinks and other harvest foods, and the hanging of lights and greens in our homes. The point is that, whether we can observe the trajectory of the death of the year in our climate or not, we do well to enhance our experience however we can of the immediacy and immanence of the eschaton.

Finally, one might ask why it's good to notice these things? Why the attention to change, to the ephemeral quality of life, to decay and death? Why the gloom and doom? Well, simply: because it's the only way to understand Christmas. And that is what the Church, in her wisdom, has set this pattern in place to do: to help guide us gradually and consistently into a deeper experience of Christ's arrival in our lives: in the past, in the present, and at the end of time. Unless we appreciate the cold, we cannot feel the warmth he brings; unless we enter into the darkness, we cannot see the brilliance of his light; unless we witness the harvest, we will not feel so compelled in our labors to bear fruit for the gathering that will one day force us to give a full account of our profitability.

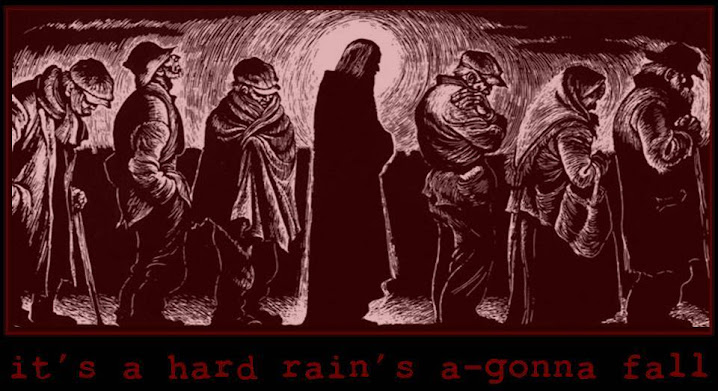

Now is different than before. These days are not entirely like the ones that have preceded them: much has passed away from them, and some things have arrived unexpectedly. And the whole importance for us is that those days before and these days now are all leading to a point: that day - that day of the prophets, the day of reckoning, the day of wrath, the day that will dissolve the world into ashes - the day when Our Lord appears. Ecce, venit.

Watch where you step.

Joe, to welcome you back to blogging, I am going to try to hit you with all the nonsense that comes at you in comboxes (a mess that's worse than goose droppings), all at the same time.

ReplyDeleteSo here goes:

* How dare you judge others!

* What, are you some liberal nut case nature loving tree hugger who pays attention to the seasons, of all things?

* I didn't really read your post, but I object to the title.

* Since the point of your post is obvious, I am going to focus on some insignificant detail that is totally beside the point: what makes you think you know how the Pagans lived and believed?

* Yes, but what do you mean by goose? And by droppings? I just don't get it. You're making so many assumptions here. Even if you explain it to me, I won't get it. Please try.